by Rev. Richard Killmer

Rev. Killmer is a retired Presbyterian minister living in Yarmouth, Maine and was the first director of the National Religious Campaign Against Torture.

Rev. Killmer is a retired Presbyterian minister living in Yarmouth, Maine and was the first director of the National Religious Campaign Against Torture.

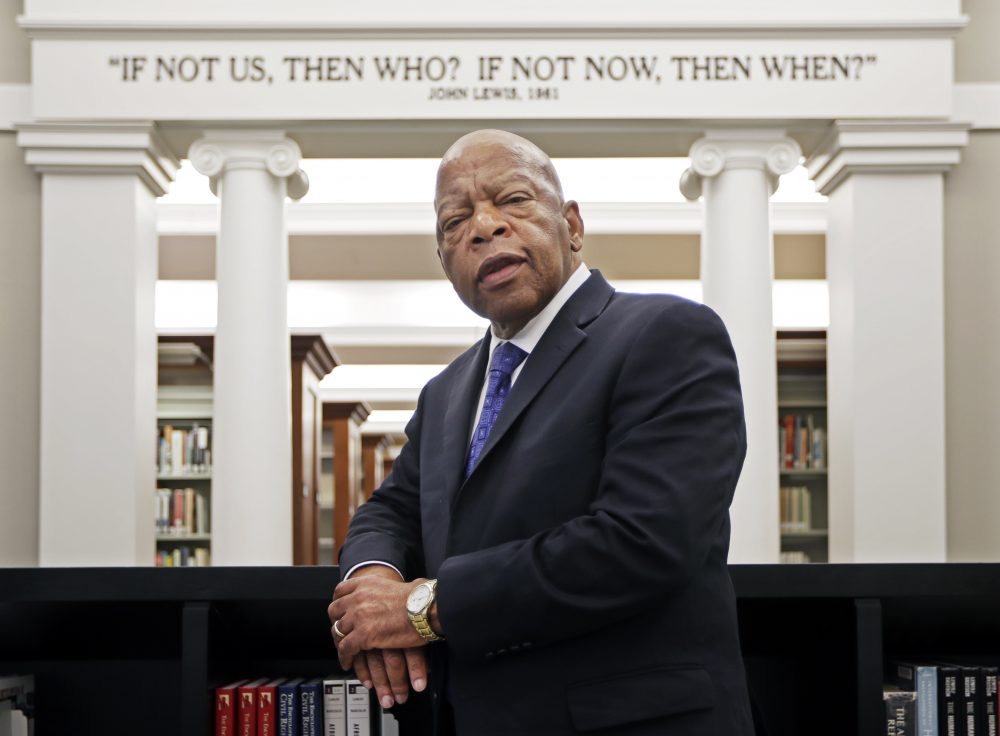

U.S. Rep. John Lewis poses for a photograph in 2016 under a quote of his that is displayed in the Civil Rights Room in the Nashville Public Library. Associated Press/Mark Humphrey

Originally posted in the Portland Press Herald.

Georgia Congressman and civil rights icon John Lewis died Friday after a career of advocating for racial justice that spanned the historic marches of the 1960s and the Black Lives Matter protests of today.

After watching video of the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, he said, “It was so painful, it made me cry.” Yet “people now understand what the struggle was all about,” he said.

“It’s another step down a very, very long road toward freedom, justice for all humankind. It was very moving to see hundreds of thousands of people from all over America and around the world take to the streets — to speak up, to get into what I call ‘good trouble.’”

“This feels and looks so different,” he said of the Black Lives Matter movement, which has led the anti-racism demonstrations after Floyd’s death. “It is so much more massive and all inclusive.” He added, “There will be no turning back.”

John Lewis became an early leader in the movement and ally of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whom he met in 1958. He was among the original 13 Freedom Riders, the African-American and white activists who challenged segregated interstate travel in the South in 1961.

Mr. Lewis led demonstrations against racially segregated restrooms, hotels, restaurants, and swimming pools. At nearly every turn he was beaten, spat upon or burned with cigarettes.

On March 7, 1965, he helped lead the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama for voting rights for African-Americans and all Americans. The first attempt of the march started when the demonstrators crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. They were met by state troopers in riot gear.

Ordered to stop, the protesters silently stood their ground. The troopers responded with tear gas and bullwhips and rubber tubing wrapped in barbed wire. During the attack, which came to be known as Bloody Sunday, a trooper fractured Mr. Lewis’s skull with a billy club, knocking him to the ground. Since I was a participant in the last day of the second attempt of the march (walking into Montgomery), we were aware that the first attempt had been met with violence by state troopers.

Mr. Lewis was arrested 40 times from 1960 to 1966. Lewis’s first arrest came in February 1960, when he and other students demanded service at whites-only lunch counters in Nashville. He was repeatedly beaten senseless by southern policemen and freelance hoodlums. During the Freedom Rides in 1961, he was once left unconscious in a pool of his own blood, after he and others were attacked by hundreds of white people.

But John Lewis’s family did not support him. When his parents learned that he had been arrested in Nashville, he wrote, they were ashamed. As a child, when he asked them about signs saying “Colored Only,” they told him, “That’s the way it is, don’t get in trouble.”

But as an adult, he said, after he met Dr. King and Rosa Parks, whose refusal to give up her bus seat to a white man was a flash point for the civil rights movement, he was inspired to “get into trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble.” Getting into “good trouble” became his motto for life.

On the other hand, President Trump, as one might expect, dismissed the current Black Lives Matter protests as having “nothing to do with justice or peace,” stating that Floyd’s memory is being dishonored by “rioters, looters and anarchists.” Good trouble is probably not something he understands.

Trump then claimed falsely on twitter, “The professionally managed so-called “protesters” at the White House had little to do with the memory of George Floyd. They were just there to cause trouble. The @SecretService handled them easily.”

It’s better to remember this 2018 tweet by Lewis: “Do not get lost in a sea of despair. Be hopeful, be optimistic. Our struggle is not the struggle of a day, a week, a month, or a year, it is the struggle of a lifetime. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.”

Originally posted in the Portland Press Herald.

After watching video of the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, he said, “It was so painful, it made me cry.” Yet “people now understand what the struggle was all about,” he said.

“It’s another step down a very, very long road toward freedom, justice for all humankind. It was very moving to see hundreds of thousands of people from all over America and around the world take to the streets — to speak up, to get into what I call ‘good trouble.’”

“This feels and looks so different,” he said of the Black Lives Matter movement, which has led the anti-racism demonstrations after Floyd’s death. “It is so much more massive and all inclusive.” He added, “There will be no turning back.”

John Lewis became an early leader in the movement and ally of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whom he met in 1958. He was among the original 13 Freedom Riders, the African-American and white activists who challenged segregated interstate travel in the South in 1961.

Mr. Lewis led demonstrations against racially segregated restrooms, hotels, restaurants, and swimming pools. At nearly every turn he was beaten, spat upon or burned with cigarettes.

On March 7, 1965, he helped lead the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama for voting rights for African-Americans and all Americans. The first attempt of the march started when the demonstrators crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. They were met by state troopers in riot gear.

Ordered to stop, the protesters silently stood their ground. The troopers responded with tear gas and bullwhips and rubber tubing wrapped in barbed wire. During the attack, which came to be known as Bloody Sunday, a trooper fractured Mr. Lewis’s skull with a billy club, knocking him to the ground. Since I was a participant in the last day of the second attempt of the march (walking into Montgomery), we were aware that the first attempt had been met with violence by state troopers.

Mr. Lewis was arrested 40 times from 1960 to 1966. Lewis’s first arrest came in February 1960, when he and other students demanded service at whites-only lunch counters in Nashville. He was repeatedly beaten senseless by southern policemen and freelance hoodlums. During the Freedom Rides in 1961, he was once left unconscious in a pool of his own blood, after he and others were attacked by hundreds of white people.

But John Lewis’s family did not support him. When his parents learned that he had been arrested in Nashville, he wrote, they were ashamed. As a child, when he asked them about signs saying “Colored Only,” they told him, “That’s the way it is, don’t get in trouble.”

But as an adult, he said, after he met Dr. King and Rosa Parks, whose refusal to give up her bus seat to a white man was a flash point for the civil rights movement, he was inspired to “get into trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble.” Getting into “good trouble” became his motto for life.

On the other hand, President Trump, as one might expect, dismissed the current Black Lives Matter protests as having “nothing to do with justice or peace,” stating that Floyd’s memory is being dishonored by “rioters, looters and anarchists.” Good trouble is probably not something he understands.

Trump then claimed falsely on twitter, “The professionally managed so-called “protesters” at the White House had little to do with the memory of George Floyd. They were just there to cause trouble. The @SecretService handled them easily.”

It’s better to remember this 2018 tweet by Lewis: “Do not get lost in a sea of despair. Be hopeful, be optimistic. Our struggle is not the struggle of a day, a week, a month, or a year, it is the struggle of a lifetime. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.”

Originally posted in the Portland Press Herald.