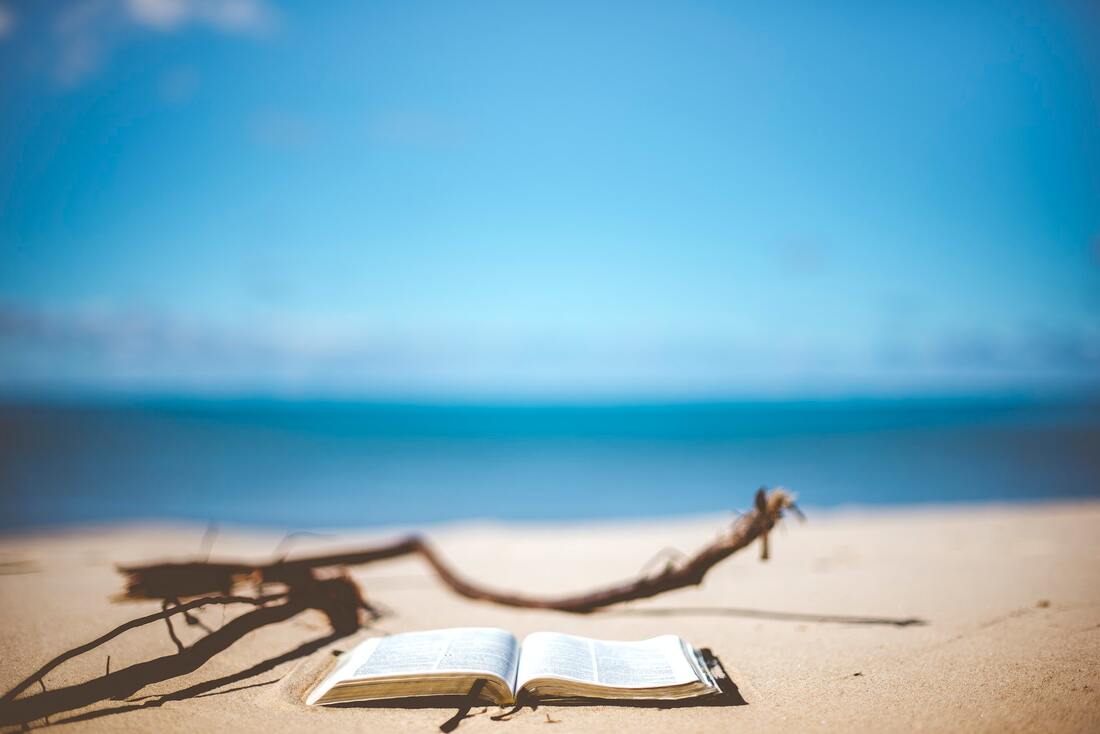

Tonight is the first night of the Jewish holiday of Hanukkah, also known as the Festival of Lights. The holiday commemorates the rededication of the Second Temple in Jerusalem after the Maccabees defeated the Syrian armies in 165 B.C.E.

A great miracle happened there – when the Jews re-entered the desecrated sanctuary, most of the oil had been deliberately defiled. But despite this, they continued searching through the rubble until they found one single sealed cruse of consecrated oil. It's important to note that it wasn't just sitting there on the floor to be found, it had to be searched for, which required faith, action, and perseverance – a perfect metaphor for 2020.

At the heart of Hanukkah is the lighting of the menorah. Each night candles are lit by the Shamash: a single flame on the first evening, two on the second, and so on until the last night of Hanukkah, when all the lights are kindled. The eight candles represent the eight miraculous nights the Temple flame burned from that single vial, which was the length of time it took to press and consecrate fresh oil.

For Jews everywhere, lighting the menorah is a reminder of God's presence in our lives:

"Why has light been such a favorite symbol of God? Perhaps because light itself cannot be seen. We become aware of its presence when it enables us to see other things. Similarly, we cannot see God, but we become aware of God's presence when we see the beauty of the world, when we experience love and the goodness of our fellow human beings." (Etz Hayim Torah commentary published by the Conservative Judaism movement, p. 503).

Seeing God’s presence in creation and community resonates across nearly every religious tradition and is central to our shared work through Earth Ministry/Washington Interfaith Power & Light. Even in the darkest hours of night – even in the most difficult days of a pandemic-filled year – there is always light. Remember that we all carry within us the spark of creation and that together we form a strong and resilient community.

LeeAnne Beres, Executive Director, Earth Ministry

https://earthministry.org/seeing-god-in-creation-and-community/

A great miracle happened there – when the Jews re-entered the desecrated sanctuary, most of the oil had been deliberately defiled. But despite this, they continued searching through the rubble until they found one single sealed cruse of consecrated oil. It's important to note that it wasn't just sitting there on the floor to be found, it had to be searched for, which required faith, action, and perseverance – a perfect metaphor for 2020.

At the heart of Hanukkah is the lighting of the menorah. Each night candles are lit by the Shamash: a single flame on the first evening, two on the second, and so on until the last night of Hanukkah, when all the lights are kindled. The eight candles represent the eight miraculous nights the Temple flame burned from that single vial, which was the length of time it took to press and consecrate fresh oil.

For Jews everywhere, lighting the menorah is a reminder of God's presence in our lives:

"Why has light been such a favorite symbol of God? Perhaps because light itself cannot be seen. We become aware of its presence when it enables us to see other things. Similarly, we cannot see God, but we become aware of God's presence when we see the beauty of the world, when we experience love and the goodness of our fellow human beings." (Etz Hayim Torah commentary published by the Conservative Judaism movement, p. 503).

Seeing God’s presence in creation and community resonates across nearly every religious tradition and is central to our shared work through Earth Ministry/Washington Interfaith Power & Light. Even in the darkest hours of night – even in the most difficult days of a pandemic-filled year – there is always light. Remember that we all carry within us the spark of creation and that together we form a strong and resilient community.

LeeAnne Beres, Executive Director, Earth Ministry

https://earthministry.org/seeing-god-in-creation-and-community/